This year was promised to be the one when New Zealand closed the income gap with Australia and stemmed the exodus across the ditch. Instead, more Kiwis than ever are heading to Australia in search of a better life. What's driving them? Cushla Norman headed to the departure gates at Wellington Airport to find out.

When former Prime Minister John Key set the 2025 goal in 2008, Australian incomes were 32 percent higher than Kiwis’. The gap has apparently narrowed: incomes are now 24 percent higher, according to Treasury figures, and yet the exodus has only increased. More on the income gap later, but first, who exactly is going to Australia and what are their main motivations?

From cop to hopeful miner

Shayne Amner is taking a punt – leaving New Zealand and his family without a job lined up across the ditch.

“It's a little bit nerve wracking. Haven't been without a job in the last 10 to 20 years," he says.

He hopes to work in a gold mine near Perth, where his partner’s younger brother also works. “He's only 21 and he's making $130,000 a year.”

The 35-year-old plans to move his family over once he’s settled in, and hopes to stay there for at least five years.

The main drawcard for him is higher wages, making it easier to get a mortgage. “Even when I was a police officer for about six years, I never got over $100,000 in that whole time.”

'You get to have a break for lunch'

Emergency department nurse Caroline Webb, 31, has 10 years’ experience but still couldn’t land a job in New Zealand.

“I applied for, I think, four jobs. And I didn't get an interview for any of them.”

She’s secured a job in Tasmania where, she says, the conditions are better. “They've got ratios, just means you have like a fewer number of patients to look after and increases patient safety and workload, and you get to have a break for lunch.”

Grandparents swap Wairarapa for Gold Coast

Ivan and Bronwyn Bratina are returning to the Gold Coast after three years in Wairarapa. They had already lived on the Gold Coast for 23 years.

They consider themselves Kiwis, but their five grandchildren were born in Australia. Seeing them grow up is the main reason they’re moving.

Watch on TVNZ+ as Kiwis at the airport explain why they're heading off.

Bronwyn says there was no negotiating as to which side of the family upped sticks. “Weather's better over there,” she laughed.

Melbourne more 'awake' than Wellington

Marketing manager Sach is catching a flight to Melbourne, having spent a month visiting family and friends in her hometown of Wellington. After a stint of living in London, Melbourne seemed like the best move, she says. "We just weren't ready to come back home yet. We had moved over to London and we were heading back. I think in terms of job opportunities and things to do, Australia kind of seemed like the best next step for us before considering coming back home."

"Wellington is an amazing city," she says. "It had so much going for it but there has been a dwindling down of activities and of places to go, our favourite restaurants shutting down."

That's not the case in Melbourne, she says. "Everything is still very much wide awake and open."

Are you moving to Australia? Tell us why - email news@tvnz.co.nz

Leaving with no intention of return

In 2024, there was a net migration loss of 30,000 people from New Zealand to Australia – the largest since 2012.

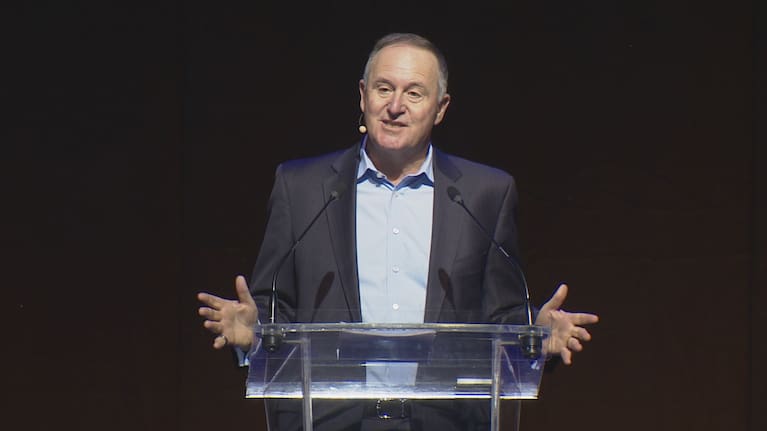

New Zealander Mark Berger has been helping Kiwis move across the ditch for the past 12 years with his online relocation service, NZRelo. He’s noticing people aren’t just treating Australia as an OE, they’re setting up homes for good.

“So, it's permanent relocations, and that's reflected with the likes of permanently moving the KiwiSaver funds across to Australia. And we're seeing a lot more older people following their children.”

Migration gathers momentum

About 600,000 New Zealand-born people live in Australia. On top of that, there’s about another 100,000 overseas-born New Zealanders there, estimates Auckland University sociology professor Francis Collins,whose focus includes international immigration.

“That's a huge draw for a lot of people who will have social connections over there.”

If people have family in a place, they’re more likely to go there, helping migration to gather momentum, he says.

John Key’s 2025 goal to close the gap

In 2008, the former National Prime Minister agreed, as part of a confidence and supply agreement with Act, to close the income gap with Australia by 2025.

Former National Party leader Don Brash was given an advisory role to Key's government and charged with coming up with ways to solve the problem. His 2025 Taskforce recommended a host of economic reforms, including cutting government spending, shaking up welfare, selling most state assets, and raising the pension age. It was rejected by Key.

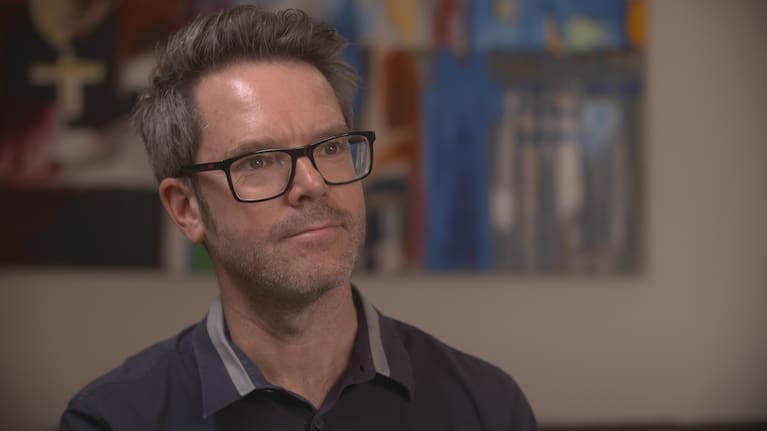

Economic commentator Micheal Reddell helped write one of the reports. “John Key found the recommendations distastefully right wing, I think it would be fair to say.

“He obviously saw that sort of thrust of recommendations as politically toxic. That, of course, was his choice. But the problem was that, having set the goal, he then didn't substitute a serious agenda for making progress his own.”

‘Ritualised bloodsport’ of blame

People voting with their feet provides endless political fodder for any opposition party.

“It's sort of a ritualised political bloodsport and they copy each other,” says Francis Collins.

Key made a big deal about emigration in the lead up to the 2008 election by standing in Wellington’s premier sports stadium to illustrate the numbers leaving to Australia.

About four years later, David Shearer, then the Labour leader, did the same thing, pointing out even more people were leaving since Key had promised to stem the tide.

In 2023, while in opposition, Christopher Luxon warned “more New Zealanders will find themselves dropping their children and grandchildren off at the airport” if urgent action isn’t taken on the economy.

These days, Chris Hipkins and Labour are making hay out of the issue. “When I speak to other parents outside the school gate or at birthday parties, one of the questions that is front of mind for all of them is, when our kids are entering the workforce, are they going to stay? When they go off and do their OE are they going to come back?” he said in Parliament recently.

But once in office it’s a different story. As Collins says: “Either there's a decision there's little we could do in [addressing the exodus], or the relationship with Australia at a kind of governmental level is too important to try and cause issues there."

Gap narrows but ‘no sustained progress’

On paper, the income gap has closed in the past 16 years from 32 percent to 24 percent. This is based on OECD numbers that compare purchasing power across countries.

But Michael Reddell says the OECD data is more useful for studying a particular point in time, rather than for tracking changes over a period because there can be fluctuations with the purchasing power parity exchange rates.

He says New Zealand has still made “no sustained progress” in closing the gap, with productivity widening slightly.

“Now, Australia is not a great productivity country itself. They've had weak productivity growth, but we've just done slightly worse than they have.”

Reddell thinks there was a missing link in the taskforce regarding the role of immigration. He suggests New Zealand adopt a less open policy, running about a third of the numbers it does now.

“What you'd expect to see if the population was growing more slowly is interest rates would be lower. Cost of capital that firms are facing would be lower. The exchange rate would be lower. And the exchange rate is the big thing that affects the competitiveness of firms thinking about exporting or competing with imports.”

Productivity matters

Reddell quotes line from economist Paul Krugman: “Productivity isn't everything but, in the long run, it is almost everything.”

He says it’s about making the most of what we’ve got. “That's natural resources, it's people, it's business opportunities that are here. If we can't make material inroads in that then we will always stay again the poor cousin, and we never were.”

'There's no quick fix'

The former chair of the now defunct productivity commission Ganesh Nana says it’s promising that the income gap has narrowed, but Australia remains a significant attraction for job seekers and retaining them is a complex, long-term challenge that would require an integrated policy programme, covering a wide gambit of issues including (but not limited to) housing, natural resources, climate adaptation, immigration, Māori/iwi and business development, health and education.

“All of these together, appropriately implemented, would be vehicles facilitating lifts in incomes for all. But it wouldn’t be quick,” he says.

A slow solution but, according to Nana, the only one. “The last thing we need is more 'siloised' policy interventions with expectations of quick returns."

SHARE ME