As Jenny-May Clarkson prepares to reveal her moko kauae for the first time on television, the Breakfast presenter tells Indira Stewart about her long road to self-acceptance and the strength she now gains from following the path of her tupuna. "It’s taken me years to finally say, this is who I am and I’m damn proud of my Māoritanga."

“I knew nothing about moko kauae growing up,” says Jenny-May Clarkson.

She's talking to me on her phone as she rides in the passenger seat of the family car, her husband Dean beside her, her mother Paddy and sister Alicia in the back seat, heading north to Ngunguru.

It’s a three-and-a half-hour drive to the small Te Tai Tokerau town where her kaitā (the artist who'll be doing her moko kauae) Reghan Anderson and his wife Kiri Peeni wait for her at their home.

Less than 24 hours beforehand Jenny-May had called to tell me she was getting her moko kauae. As her friend, I was both excited and nervous for her. As a reporter, I feel inadequate for the task of writing about this significant taonga, a momentous step.

In recent years I’ve watched Jenny-May as she’s navigated her way towards reclaiming her Māoritanga. As a TVNZ Breakfast presenter, it’s a journey she’s had to take in the public eye – at least parts of it. The real lead up to this day has taken decades.

When I call that Saturday morning, Jenny-May is still processing what’s to come when she arrives at the home of her kaitā. It’s a long drive and talking is a great way to soothe the nerves, so we start with her childhood.

“I don’t remember seeing many of our kuia wearing kauae,” recalls Jenny-May. “But when I did see it, there was strength about them, an authority and a knowing. It made me feel like I was home.”

That feeling is tau, she says. A sense of feeling settled.

In the months and years leading up to this day, just like on this drive, Jenny-May has felt that strength and comfort, but other feelings too. Curiosity, fear, anxiety.

While making the decision to get her moko kauae, Jenny-May spoke with a handful of key people. One of her aunties recalled what it was like in Aotearoa back in the 1950s and 60s for some of their nannies who wore moko kauae. The whakamā and stigma attached to it by society. She remembered how some kuia were so ashamed of their moko kauae they wouldn’t leave their homes, and how people would literally cross the road to avoid a woman with a moko kauae. She particularly recalled one, sitting on the side of the road, her head bowed, wrapping a scarf around herself to hide her face.

Jenny-May's great grandmother is the only tupuna that her family can remember who wore moko kauae. It would be decades before an auntie, her father’s sister, would claim hers.

“Kauae was a mystery to me,” says Jenny-May. “And yet when I saw it, it felt like something magical and beautiful. Whenever you saw those nannies with their kauae somehow you knew that you were a part of them. And they were a part of you.”

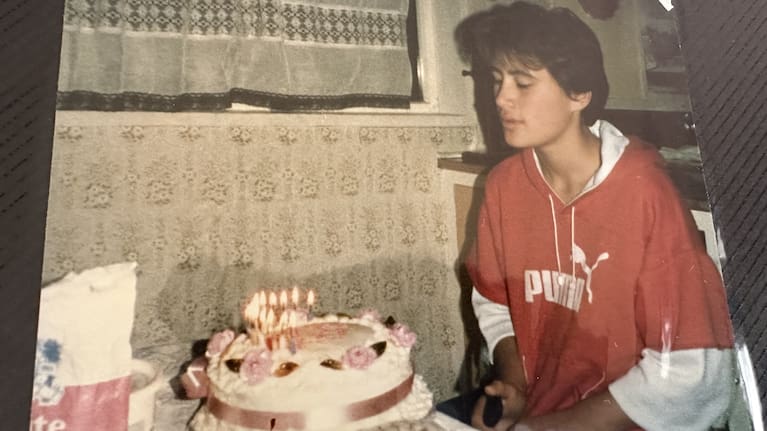

As a little girl, did she ever wonder about the possibility of a moko kauae for her future self? “Never,” says Jenny-May. “That’s because I didn’t want to be Māori.”

“As a child I loved experiencing kapa haka in school,” she says. “But as I grew older, I began to see a different side to how Māori were treated and perceived in the world I knew, which was mainly a Pākehā world.

“By the time I’d reached my teenage years in Piopio, I refused to acknowledge that I was Māori.”

Piopio, a town in the Waitomo district, was a small farming community in the 1970’s. It was also where Jenny-May’s late father, Te Waka Coffin, was raised. Te Waka refused to give his children Māori first names because of how his own name was made fun of when he was growing up. “As a teenager trying to find my own identity, what I saw and experienced about being Māori painted a negative picture about who we were as a people. And I didn’t want to be labelled like that,” says Jenny-May.

“So, I never thought a moko kauae was for me.

“I’d love to tell that confused little kid and her older teenage self: one day you will love yourself. That feeling you get when you stand on stage proudly wearing your kapa haka kākahu, belting out waiata, that feeling of pride and belonging, will remain with you. That little hōhā kid running around at the marae, will remain within. You are everything your tupuna dreamed you would be. So hold your head high.”

More than 30 years later, when Jenny-May arrives in Ngunguru her kaitā will pick up his tools and pierce her chin, opening up a whole new world. She’s ready for it.

“Hearing my auntie talk about her experiences of seeing moko kauae strengthened me for what could potentially come for myself,” she says.

“I made my decision a long time ago but I’ve never been on anybody else’s timeline. I did my own work internally and it’s taken me years to finally say – you know what? This is my line in the sand. This is who I am and I’m damn proud of my Māoritanga, who I’ve become and who I want to be. I’ve come full circle,” she says.

“After today there’ll be no mistaking who I am.”

He Ao Hou. A new world

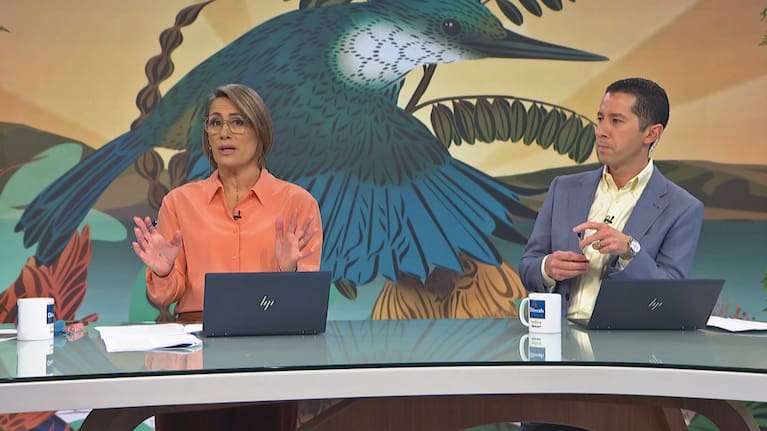

"It’s taken me years to finally say this is who I am and I’m damn proud of my Māoritanga." (Source: 1News)

‘I can see the emails’

“I had a terrible sleep,” Clarkson tells me over the phone the next day – the first morning she has woken up with her moko kauae.

“Just very real doubts started to creep in. What is everybody going to say? I don’t want to go back to work, you know. I can see the emails, I can see the responses already and all of that was just going through my head.

“I finally got to sleep and woke up at around 6:30 and I just lay there. And all of a sudden this calmness came over me and those thoughts just left,” she says.

“I can’t even explain to you how it all just lifted but it was gone.”

Receiving her moko kauae was an intimate moment Jenny-May wanted to share with just her husband Dean, Mum Paddy and older sister Alicia. But she’d taken a photo of her siblings and father, and one of her grandmothers – who her auntie told her would be with her on this journey.

“I thought about my grandmother as Reghan talked me through the process,” she says. “We spoke about the different patterns and collaborated on the final design.

“Once I was settled, I lay down and my husband and sister draped our Clarkson whanau kākahu over me. They then placed my mother’s kākahu, which is over 70 years old, on top. Reghan said our karakia and away we went.

“I just closed my eyes and pictured my grandmother’s face. Her soft eyes, her round face, that twinkle in her eye. I wondered how proud she would be.”

Then there were the first piercings of the kaitā’s needle, marking the story of her whakapapa on her skin. The design of a kauae, Jenny-May explains, can include a range of details including where you’re from and your place in your whānau.

“My kauae represents both my mum and dad. Mum from Ngāti Kahu and my dad from Ngāti Maniapoto, although my son says the four koru represent him and his brother, Dean and me. I like his thinking,” she says.

“I couldn’t talk so I just kept my eyes closed and kept listening. I could hear the conversations between my whānau and the kaitā’s wife Kiri. Kiri shared about her own experience with her moko kauae helping my mum and sister understand the process. My kaitā Reghan jumped in and said it was a really quick way to ‘weed out the garden’.”

That is, the garden that represents your life, and the people within it. “He said that when you start to wear the moko, you’ll know who is with you and who isn’t. And that happens very quickly.

“Both Mum and my sister have sat with their own feelings and thoughts about my moko kauae for weeks, acutely aware of how people might respond to it. They’ve watched my journey connecting to who I am as a Māori woman on a public platform and they’ve seen some of the comments I’ve received in reaction to that.

“But Mum also understood that I, her youngest child, am very stubborn and will do what I want. I think that uncertainty and fear that Mum had for me disappeared while I was getting my kauae because she was a part of that process.”

When the kaitā had finished, Jenny-May sat up on the table smiling and then was immediately overcome with emotion.

“I don’t know where it came from but I allowed it to consume me for a moment. I allowed myself to feel the moment and my connection to my grandmother and my tupuna. I felt relieved that I’d chosen to do this privately so I could be vulnerable and safe in that space with just my whānau.

“And then I got up looked in the mirror at my new mate and I just couldn’t stop smiling.”

‘Too late to turn back now’

“Can we kiss you?”

“Can you rub it off? Or is that it?”

The reaction of Jenny-May’s eight-year-old twin boys Te Manahau and Atawhai to their mama’s moko kauae is filmed by their dad Dean.

Moko kauae is a normal part of the boys’ world. Many of their kaiako at kura wear mataora and moko kauae.

“Yeah, nah. I like it. Looks good,” says Te Manahau.

Atawhai is hugging Dean from behind and staring thoughtfully, “It looks different to what I thought it would look, but I like it. Well, too late to turn back now’” he says.

And Jenny-May knows this. She’s taken the week off work to get used to her new ‘mate’ as she calls her moko kauae. The first time she stepped outside the house she was full of nerves. “The thoughts were: What will people think? How will they look at me? What will they say?”

She journaled her experience that day:

I jumped into a lift full of people – most of them looked down or looked away. I smiled and held my head up with a soft gaze, scanning the lift with my peripheral vision. Who was most uncomfortable? Them or me?

I look at people and my place in the world differently. I don’t want people to be afraid. I want people to ask questions. I want to help them understand “her” – my new mate. I would want to stare. I would want to touch. I would want to know the story behind it. So why shouldn’t they feel the same?

It feels like a new world and we walk together now – me and her. I’m grateful to have time to explore what this world now looks like for us, before I share her with my Breakfast whānau and the world.

“I'm still the same person,” Jenny-May tells me. “And I know some people won't be able to see through my kauae and that’s okay.

“Everybody is on their own journey and I understand if perhaps some members of our audience find it abrasive. But this is still me. I just choose to wear who I am now.”

Jenny-May acknowledges she’s not the first wahine Māori to wear moko kauae on mainstream television. Oriini Kaipara paved the way back in 2019 when she presented 1News Midday show on TVNZ.

“Her grace and strength throughout that tumultuous time was extraordinary and I honour her unwavering courage and bravery,” says Jenny-May.

Today (Sunday) marked the most important part of Jenny-May sharing her moko kauae. She returned to Piopio, back to her marae at Mōkau Kohunui to be welcomed home by her own.

And yesterday she visited her tupuna who lay at rest in their whanau urupā (cemetary). “My grandmother, great grandmother and of course my dad,” says Jenny-May.

“It rained heavily all the way there but, as we entered, the rain softened and for the 10 minutes of our visit, it stopped. I choose to believe that was a sign that they were happy and agreed with my decision. I went to my great grandmother first then my grandmother and made my way to my dad. I usually feel a sadness overwhelm me when I sit with my dad but today I felt light and tau. I said, ‘What do you reckon Dad?’ And as I did, I smiled. I reckon he’d be proud of me knowing my journey, his journey, our journey.”

Portraits of Jenny-May Clarkson with moko kauae by Jessie Casson (@JessieCasson).

SHARE ME